Total War Comes to the Chesapeake

As a continuation of our series of Local Interest Articles, we continue with more of the War of 1812 that has interest to our local area.

For the first part of the War of 1812, the British pretty much kept away from the Chesapeake region, preferring instead to keep fairly close to their American base of operations in Halifax. However, with the start of the 1814 campaigning season, a new commander, in the form of Sir Alexander Cochrane, arrived on the scene. Cochrane had the idea that harsh treatment of civilians would somehow help the British war effort.

For the first part of the War of 1812, the British pretty much kept away from the Chesapeake region, preferring instead to keep fairly close to their American base of operations in Halifax. However, with the start of the 1814 campaigning season, a new commander, in the form of Sir Alexander Cochrane, arrived on the scene. Cochrane had the idea that harsh treatment of civilians would somehow help the British war effort.

Up to that time, there had been occasional atrocities against civilians by both sides, but these were small-scale and against standing orders. Most of these were on the frontier, the often ill-defined border between the American settlements, British Canada, and Indian Territory. The intentional burning of Newark (now Niagara-On-The-Lake) by Canadian troops who had switched sides to fight for America, and the sacking and burning of York (now Toronto) were two examples of the American side letting things get out of hand. However, on the Chesapeake in 1814, there began under Cochrane an official “scorched earth” policy.

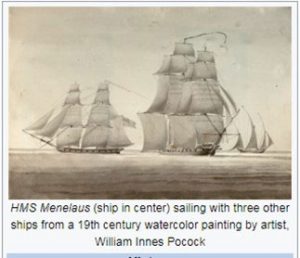

One of the British commander’s favorite arsonists was Sir Peter Parker (Baronet), captain of the frigate Menelaus. Parker, who was the son, grandson, and great grandson of distinguished naval commanders, thirsted for glory and advancement, and eagerly accepted the charge to burn every house that harbored a militia man. The test for harboring a militia man was relatively simple: if a firearm was found, the house was burned. In an era in which every home had a muzzle loading duck gun or hunting rifle, this standard insured a fine day of arson and presumed glory for the young vandal Parker.

One of the British commander’s favorite arsonists was Sir Peter Parker (Baronet), captain of the frigate Menelaus. Parker, who was the son, grandson, and great grandson of distinguished naval commanders, thirsted for glory and advancement, and eagerly accepted the charge to burn every house that harbored a militia man. The test for harboring a militia man was relatively simple: if a firearm was found, the house was burned. In an era in which every home had a muzzle loading duck gun or hunting rifle, this standard insured a fine day of arson and presumed glory for the young vandal Parker.

After a few incursions in the middle Bay area, mostly around Annapolis, Parker was detailed to the upper Eastern Shore in an attempt to keep militia troops from crossing the Chesapeake to go to the aid of Baltimore while the main British forces practiced their skill in setting fires during the sack of Washington.

By August 1814, Sir Peter Parker was merrily torching homes, barns, and anything else considered “of value” in the area between Rock Hall and the Sassafras River. On August 28, they burned the farm of Henry Waller near Worton Creek, including house, barn, outbuildings, and wheat in the granary, to the tune of about 8-10 thousand dollars of 1814 era money. On the 30th Parker returned to burn the farm of Richard Frisby, which adjoined Waller’s.

By August 1814, Sir Peter Parker was merrily torching homes, barns, and anything else considered “of value” in the area between Rock Hall and the Sassafras River. On August 28, they burned the farm of Henry Waller near Worton Creek, including house, barn, outbuildings, and wheat in the granary, to the tune of about 8-10 thousand dollars of 1814 era money. On the 30th Parker returned to burn the farm of Richard Frisby, which adjoined Waller’s.

Unfortunately for Parker, some of his men (or maybe it was Parker himself) boasted that they were coming ashore that night to destroy the local militia headed by Lt. Col. Philip Reed. True enough, that night they landed 124 sailors and marines to sweep away the opposition. Heading inland from the beach near Tolchester, they followed 2 local guides, black men who were described as “unreliable”, but who may well have been working for the benefit of the American forces. These guides led the British contingent to a clash with the militia at Isaac Caulk’s field, about 2½ miles inland.

At the first press of battle, the American center retreated, and the British rushed forward to claim their victory. Lt. Col Reed, however, was an experienced fighter, having achieved the rank of Captain of Infantry in the Revolutionary War. He had also been a U.S. Senator before the War of 1812. Reed was a crafty fighter, and pulled back the center of his line, but only for a short distance, drawing the enemy forces into a box. The American center then turned and fired, as did the remaining militia troops on both right and left flanks. Reed even had a few small fieldpieces, though with only enough powder for a few rounds. Caught in the crossfire, with their opponents firing from three sides, the British seadogs lost 13 dead and 28 wounded. According to reports, an additional 40 of their number slipped away in the darkness and confusion and deserted, for a total loss to the Menelaus of somewhere around 75. The American militia, in perhaps their most successful fight of the war, suffered 3 wounded.

At the first press of battle, the American center retreated, and the British rushed forward to claim their victory. Lt. Col Reed, however, was an experienced fighter, having achieved the rank of Captain of Infantry in the Revolutionary War. He had also been a U.S. Senator before the War of 1812. Reed was a crafty fighter, and pulled back the center of his line, but only for a short distance, drawing the enemy forces into a box. The American center then turned and fired, as did the remaining militia troops on both right and left flanks. Reed even had a few small fieldpieces, though with only enough powder for a few rounds. Caught in the crossfire, with their opponents firing from three sides, the British seadogs lost 13 dead and 28 wounded. According to reports, an additional 40 of their number slipped away in the darkness and confusion and deserted, for a total loss to the Menelaus of somewhere around 75. The American militia, in perhaps their most successful fight of the war, suffered 3 wounded.

Lt. Col. Reed went on to election to the House of Representatives and served from 1817 to 1819. Sir Peter Parker (Baronet) returned home to England, his body preserved in a cask of rum. It was alternately said that he died instantly from a head wound, or else bled to death from a buckshot wound in the femoral artery. It turned out that he had been right all along, and that muskets used for hunting ducks actually were weapons for the militia. Private Henry Urie was reported to have shot Parker from his post in the overhanging branches of a large willow tree, using a blunderbuss “loaded to the muzzle with all the hardware, bolts, nuts, nails, etc., in his barnyard.”

Today, the battlefield on Caulk’s Field Road, about 2½ miles from Tolchester Marina, is pretty much unchanged from 1814. It is still a planted field, but is marked by a granite monument flanked by flagpoles flying the American flag and the Union Jack.